The Architectural Shift: Moving to MikroORM's Unit of Work

If you’re coming from the Prisma or TypeORM ecosystems, MikroORM often feels alien. You might find yourself fighting the EntityManager, confused by flush(), or debugging why your changes aren’t persisting.

The friction you’re experiencing isn’t syntactical. It is architectural.

Prisma acts primarily as a Table Data Gateway—you ask for data, you get plain objects. TypeORM attempts the Active Record pattern but often devolves into ad-hoc query building.

MikroORM implements the Data Mapper pattern, centered around two critical concepts: the Unit of Work (UoW) and the Identity Map.

This post explains why these patterns exist, the trade-offs they introduce, and how to operate them correctly in a concurrent Node.js environment.

The Paradigm Shift: Managed State

In a query-builder world (Prisma, Knex), the mental model is stateless:

- Construct query.

- Send to DB.

- Receive disconnected data.

Every call is isolated. If you fetch row-123 twice, you get two distinct JavaScript objects. Modifying one has no effect on the other.

In MikroORM, the EntityManager is stateful. It doesn’t just “fetch” rows; it manages them. When you load an entity, the EntityManager tracks it.

The Identity Map: Referential Integrity in Memory

The Identity Map ensures that for a given EntityManager scope, a unique database row corresponds to exactly one JavaScript object reference.

// Prisma/TypeORM: Divergent state

const a = await repo.findOne({ id: 1 });

const b = await repo.findOne({ id: 1 });

console.log(a === b); // false

// MikroORM: Convergent state

const x = await em.findOne(User, 1);

const y = await em.findOne(User, 1);

console.log(x === y); // trueWhy this matters:

In complex domains, you pass entities through multiple service layers (validation, policy checks, mutation). Without an Identity Map, you risk a “split-brain” scenario where Service A modifies one copy of User:123, Service B reads a stale copy of User:123, and the last write wins (or worse, you get partial data corruption).

With MikroORM, every service in the request scope observes the exact same instance.

The Unit of Work: Implicit Transactions

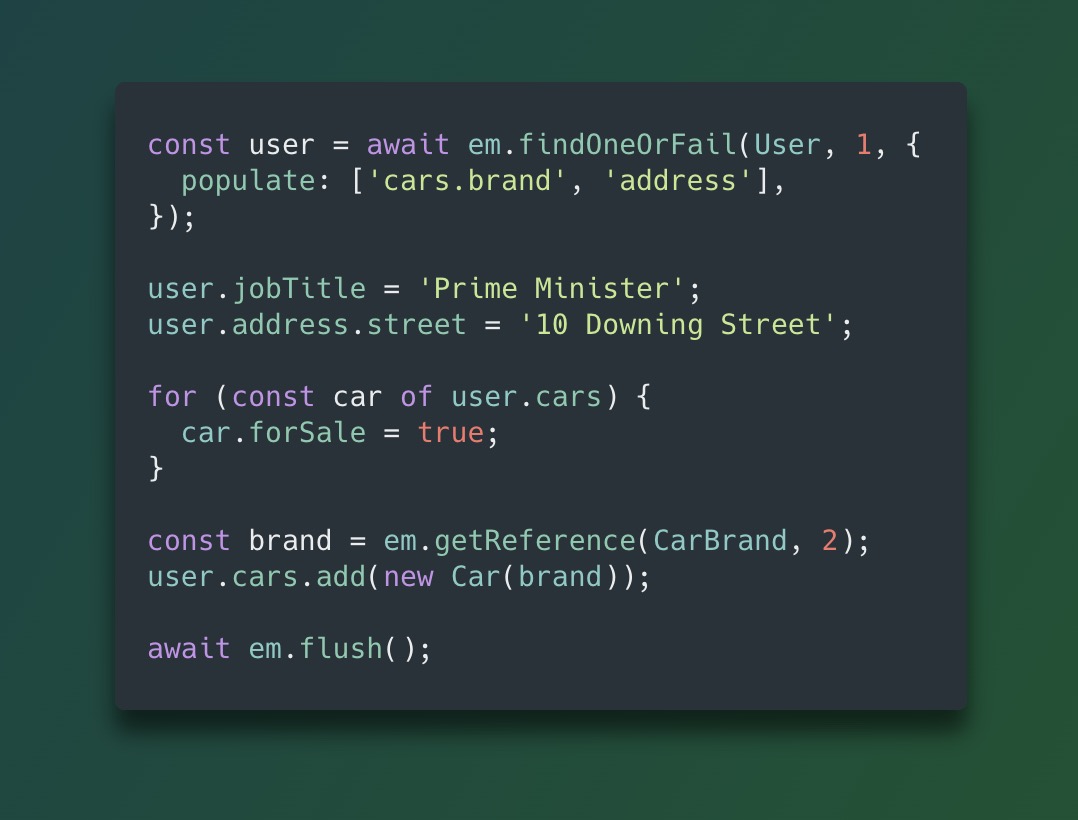

The Unit of Work pattern decouples mutation from persistence.

Instead of calling save() essentially being a single INSERT/UPDATE statement, you modify your objects in memory. The UoW tracks these dirty states. When you call flush(), the system calculates the most efficient way to persist the net changes.

The benefits are non-trival:

- Write-Behind: Database I/O is deferred until the logical operation is complete.

- Atomicity: Multiple related changes (e.g., creating an Order and its OrderItems) are flushed together, typically in a single transaction.

- Batching: The ORM can group INSERTs and UPDATEs, reducing network round-trips.

Context Propagation in Node.js

The challenge with stateful ORMs in Node.js is concurrency. In a blocking language like Java or Python (with Flask/Django), “one request” often maps to “one thread.” You can store the EntityManager in thread-local storage.

Node.js is single-threaded and asynchronous. Requests are interleaved. If we store the EntityManager in a global variable, Request A might flush Request B’s partial state.

Strict Consistency is Required

To make this work, we need AsyncLocalStorage. This is what MikroORM’s RequestContext provides. It allows us to fork a specific EntityManager for a request and ensure that every await down the chain can access that specific fork.

The Implementation Pattern

Do not use the global orm.em in your business logic. It allows cross-request pollution.

The Golden Rule: Every request must have its own fork.

1. Middleware Setup

In Express/Fastify/NestJS, you must ensure a context is established before any logic runs.

// express-middleware.ts

export const withOrmContext = (orm: MikroORM) => (req, res, next) => {

// 1. Fork the EM (Create clean state)

// 2. Wrap the downstream stack in a specific context

RequestContext.create(orm.em.fork(), next);

};2. Access Patterns

There are two ways to access this context.

Pattern A: Dependency Injection (Preferred)

Pass the EntityManager explicitly through your layers. This makes transaction boundaries obvious and testing easier.

// Explicit implicit dependency

class UserService {

constructor(private readonly em: EntityManager) {}

async upgradeUser(userId: string) {

const user = await this.em.findOneOrFail(User, userId);

user.plan = Plan.PRO;

// No flush here? Better to let the controller flush,

// or use explicit transaction scoping.

}

}Pattern B: Static Access (The Escape Hatch)

For legacy codebases or deep utility functions where prop-drilling is unfeasible, RequestContext.getEntityManager() allows you to reach into the current async scope.

import { RequestContext } from '@mikro-orm/core';

export function getCurrentUser() {

const em = RequestContext.getEntityManager();

// ... operations

}Advisory: Overusing static access couples your domain logic to the framework’s runtime environment. Distinct isolation becomes harder.

Pitfalls & War Stories

1. The “Ghost” Flush

Because flush() persists all managed changes in the context, you can accidentally persist data modified by a completely different service if you share the context broadly.

Mitigation: Use em.transactional() blocks to isolate logic and ensure you only flush what you intend to, or strictly follow “flush at the end of the request” patterns.

2. Fork Mixing

Never mix entities from different forks.

const globalUser = await globalEm.findOne(User, 1);

const requestUser = await requestEm.findOne(User, 1);

globalUser.name = 'Dave';

await requestEm.flush(); // Nothing happens to globalUserThis is a common source of “why didn’t my data save?” bugs.

3. Background Jobs

Queues (BullMQ, SQS) do not have an HTTP middleware layer. You must manually wrap your job processors in RequestContext.createAsync or manually manage the fork/flush lifecycle. Failing to do so causes memory leaks (the identity map never clears) and eventual crashes.

Summary

MikroORM trades “ease of start” for “correctness at scale.”

By forcing you to acknowledge the Unit of Work and Request Context, it prevents an entire class of concurrency and consitency bugs common in simpler ORMs. It demands you understand the lifecycle of your data: where it is loaded, who owns it, and when it is persisted.

Embrace the fork. Respect the context.